M&A in the Permian Basin: Heart of the U.S. Shale Boom

The Permian Basin: A bright spot in a muted M&A environment

In the past year, energy investors have pressured companies to “live within their means” and focus on delivering returns. As a result, the pace of deals has slowed in the first quarter of the year as many companies prioritized trimming their balance sheets before making new acquisitions.

If oil prices continue to trend upwards, investor pressure may subside as profits start to rise. Major producers, including BP, Chevron, and Occidental Petroleum—one of the largest operators in the Permian—reported solid first quarter earnings, momentum that investors hope will continue.

Doubling down in the Permian

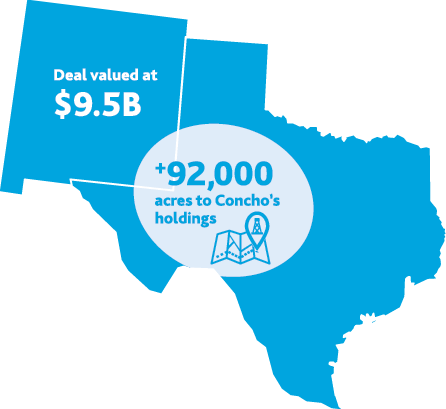

At the tail-end of the first quarter of 2018, Concho Resources Inc. bought RSP Permian in the biggest deal in the Permian Basin’s history.

The transaction, expected to finalize in the third quarter, would establish Concho as the largest active driller in the Permian. Concho aims to leverage the scale of its and RSP’s combined operations to drive down costs and increase returns.

The Concho-RSP deal might be the tip of the iceberg for similar deals motivated by the opportunity to leverage scale as a hedge against unpredictable prices.

Is this the end of an M&A dry spell for energy, or just the Permian?

While dealmaking could slow in the energy sector overall, the Permian operates on its own terms.

While dealmaking could slow in the energy sector overall, the Permian operates on its own terms. Permian players may find mergers a viable strategy for driving down costs and increasing returns. Following the logic of the Concho-RSP merger, more Permian producers may buy their competitors to create and leverage scale to drive down transportation and production costs.

At the start of Q2, Marathon Petroleum announced a $23 billion deal to buy the refining company, Andeavor, which has a significant presence in the Permian. The merger would link Andeavor’s assets in West Texas and New Mexico with Marathon’s transportation infrastructure and refineries on the Gulf Coast and in the Midwest. Like Concho-RSP, the combined entity will similarly look to leverage scale to lower logistics costs and drive up returns from Permian-based production.

The Permian’s rise to prominence

Let’s back up. How did the Permian heat up?

During the oil downturn of 2014, companies were hard-pressed to find methods and areas that had lowproduction costs. Saudi Arabia, OPEC, and Russia thought that depressed oil prices would shut down capital-intensive shale operations. But thanks to recent innovations and the thickness of its shale formations—10 to 15 times that of other shale formations—the basin has led the way in the U.S. production surge.

Why the Permian?

In a nutshell – Permian companies spend the least amount of capital to get the most reserves out of the ground. The Permian Basin is now the second largest oil field in the world behind Saudi Arabia’s Ghawar Field by output.

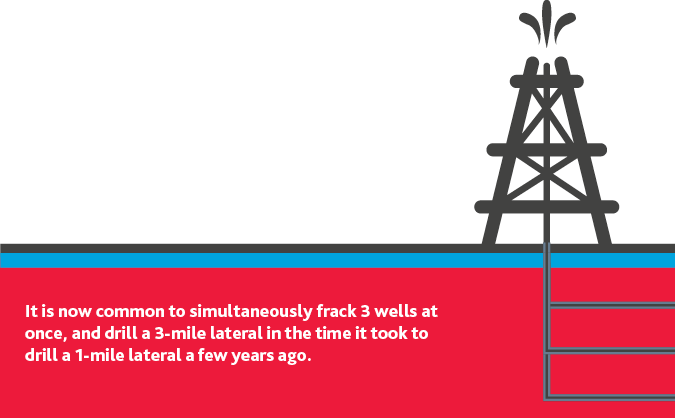

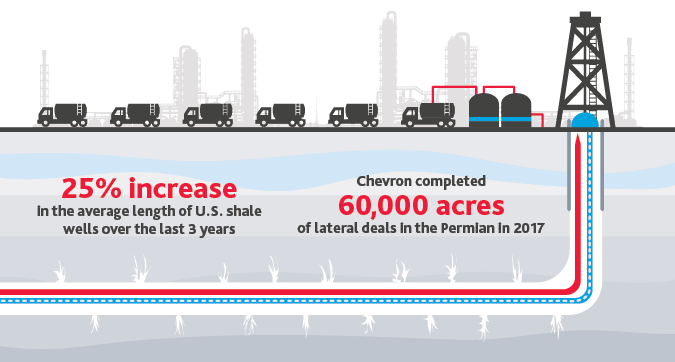

Advancements in horizontal drilling efficiencies have allowed producers to dramatically increase the speed and scope of production, making the Permian one of the most profitable areas for shale production.

|

Over 29 billion barrels of oil have been produced in the Permian since output began in 1921 | |

|

The Permian stretches 250 miles wide and 300 miles long | |

|

Breakeven price is less than $30 a barrel in the Permian |

History of dealmaking in the Permian

In recent years, increased land purchases followed the development of new techniques that allow producers to drill longer wells more quickly.

Large, contiguous blocks of acreage are strategic, given recent advances in horizontal drilling. In 2016 and 2017, companies bought their neighbors or swapped and sold land in exchange for land closer to their existing acreage. In 2016, Concho spent $1.63 billion for 40,000 acres in the Midland basin, and another $430 million for land on the Delaware side of the basin. RSP previously bought Silver Energy Partners and Silver Hill E&P for $2.4 billion.

Too much of a good thing?

Low oil prices and a desire to compete globally drove initial innovations in U.S. shale drilling.

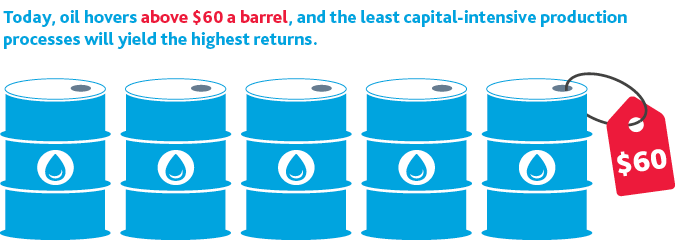

Low oil prices that initially created incentives to innovate have stabilized, and companies in the region have a singular focus: ramping up production to capitalize on recovered prices.

If research and development is neglected in the production frenzy, the Permian could exhaust its most easily accessible resources before new technologies are developed that allow companies to extract a higher percentage of resources out of the rock.

If Permian producers grow complacent, other drilling methods or newly-discovered reserves may decrease their competitiveness.

There’s a world beyond the Permian.

Which other basins could rise in the ranks?

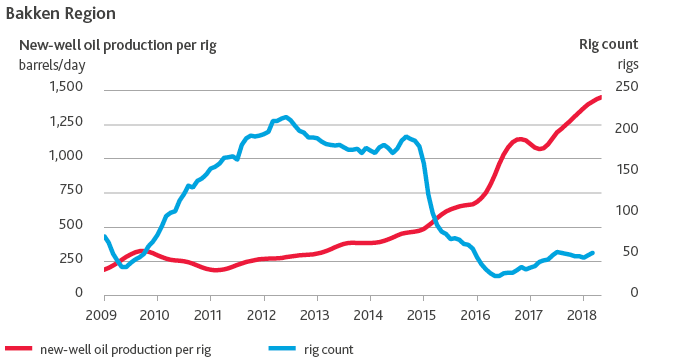

Source: U.S. Energy Information Administration

Production in the Bakken Shale Play, located on the border of North Dakota and Montana, has slowly recovered in recent years due to climbing oil prices and innovations in shale drilling.

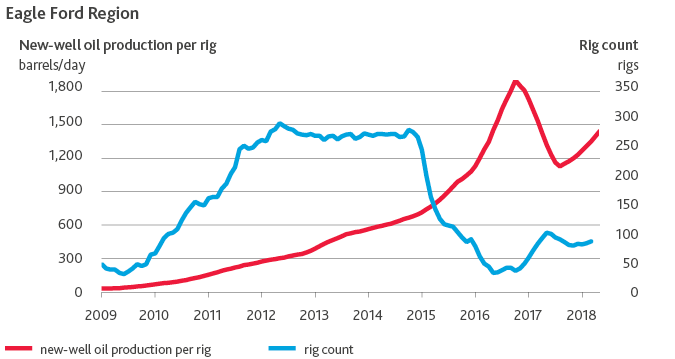

Source: U.S. Energy Information Administration

The confluence of climbing oil prices and drilling innovations has led to a similar trend in the Eagle Ford Shale, which is located primarily in southern Texas.

Bakken, Eagle Ford, or another US basin, may emerge as fierce competitors to the Permian in the future. The Permian may hold the U.S.’ shale-producing crown for the foreseeable future, but as recent years have taught, nothing in shale lasts forever.

Have Questions? Contact Us

SHARE