Demystifying Valuation Methodologies: Part 4 - Contingent Value Considerations

Introduction

Earnouts and contingent value rights (both referred to as “contingent value”, “contingent value rights,” or “CVR”) have become increasingly popular instruments to bridge the valuation gap between buyers and sellers, particularly for biotech M&A and even some private equity backed technology transactions. In fact, they are becoming commonplace in portfolios of life science focused fund investors (who previously held investment stakes in life science start-ups that have since been acquired, in some cases, by large biopharma companies). For purposes of this article we will refer to holders of contingent value who receive contingent value instruments in exchange for the consideration of their ownership in a company that is sold as “fund investors”.

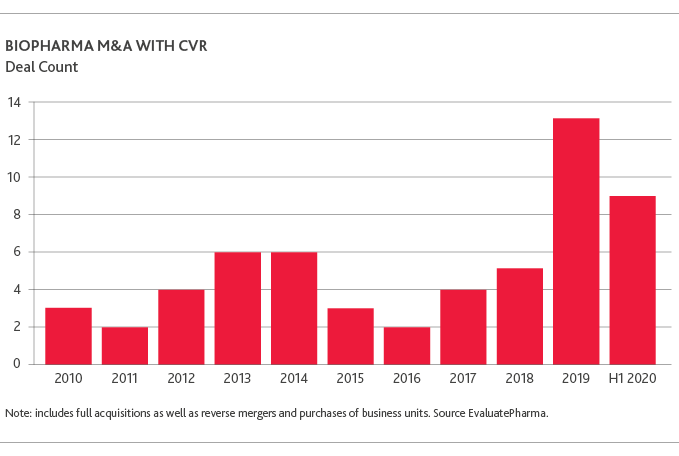

The chart below highlights notable biopharma deals concluded to date whose deal value includes a significant element of contingent value (source: Evaluate Vantage “Contingent value is back in vogue”, Aug. 12, 2020)

As the trend towards contingent value continues to gain traction and, given the highly volatile and subjective nature of these instruments (as well as their potential impact on financial statements), contingent value considerations deserve special attention, particularly from the perspective of the fund investor holding them.

Within this article, we will address the basic concepts of contingent value instruments, focus on CVRs that are carried at fair value and discuss certain subjective key inputs that drive their fair value and highlight a few important considerations for fund investors to consider as they prepare their financial statements (annual and interim).

Overview

Generally speaking, contingent value instruments provide a fund investor with a call option whose present value is contingent upon achieving future milestone(s). In biotech transactions, contingent value rights are typically structured as either lump sum payments or payment-in-kind (with shares) triggered once a specific milestone is achieved (e.g., generally beginning with regulatory pre-approval of a drug). In other deals such as select private equity technology transactions, earnouts are sometimes contingent on hitting some level of EBITDA (or other financial metric) performance.

We recognize contingent value instruments can vary widely in terms, structure, and size. The expiration dates of these instruments vary widely and are negotiated on a deal-by-deal basis with some contingent value rights lasting for 10 years. For simplicity purposes we will address contingent value with our focus tilted more towards practical considerations, specifically for fund investors holding these instruments.

For a more thorough understanding of contingent value inputs, we would refer readers to the guide prepared by The Appraisal Foundation titled Valuations in Financial Reporting Valuation Advisory 4: Valuation of Contingent Consideration, (“VFR 4”), which is considered the industry standard for valuation of contingent value instruments by valuation professionals. The AICPA guide titled Valuation of Portfolio Company Investments of Venture Capital and Private Equity Funds and Other Investment Companies also devotes specific pages to the valuation of contingent value instruments (see Q&A 14.24 and Case Study 12 within the AICPA guide).

Ultimately, Accounting Standards Codification (ASC) Topic 820, Fair Value Measurement, is the authoritative standard under US GAAP when determining the fair value, and while the guides referred to previously are non-authoritative, where CVRs are carried at fair value, they apply the concepts of ASC 820 to contingent value instrument valuation and provide illustrative examples.

Key Valuation Inputs

Within the context of contingent value calculations, it is important to understand where specific risks exist. Prime examples of these risk areas can include the risk of achieving certain milestones, risk associated with underlying financial performance forecasts and risk of non-payment. While several of the risks inherent in contingent value calculations can be isolated, it is important to understand these risks collectively and if there is interdependence between each.

I. Probability Weightings

One of the most subjective inputs in a contingent value calculation is the probability weighting assigned to each future milestone. For example, in the case of biotech milestones, in a perfect world it would be ideal for a fund investor to look back at historical FDA pre-approval/approval of similar drugs and apply an approval percentage to the probability weighting of that milestone. As with any forward-looking prognostication, the past is not necessarily a predictor of the future and each circumstance is unique and different. In reality, deriving probability weightings for contingent value is a full faith best effort process often based on the judgement or experience of management.

For fund investors holding contingent value instruments, it is important to maintain some degree of consistency in their valuation policy given the subjective nature of these probability weightings. For example, if an investor generally has a higher degree of confidence in the pre-approval of certain drugs, it important to carefully document the reasoning underlying these assumptions, especially for calibration and back-testing purposes. By documenting the rationale behind certain probability weighting thresholds, fund investors will have a basis for the judgement in their determination and assessment that supports the valuation of these instruments in the financial statements.

II. Expected Term

The expected term in a contingent value calculation is the future date when the specific milestone is expected to be achieved or the time frame over which performance will be measured. The expected term determines the present value factor to be applied to the future cash flows. In some situations, the future cash flows associated with a milestone may not be paid until a specific date is reached as outlined in the purchase and sale agreement (“P&S agreement”). In such instances, the valuation may be relatively straightforward given that the expected term is fixed.

In other cases, such as in the case of biotech milestones, the future cash flow is tied to a milestone subject to the occurrence of an event (e.g. regulatory approval and the future cash flow would be paid once that approval is obtained). However, the estimate of when that regulatory approval is expected to occur is highly subjective. Therefore, it is important to understand the specific terms of each milestone in the P&S agreement in order to gain a better understanding of the expected timing of the actual payment. Fund investors should ensure they clearly document considerations behind the expected term determination for contingent milestones, taking into account any potential delays in the timing of a payment once a milestone is achieved.

III. Discount Rate

As with any discounted cash flow calculation, the discount rate employed to discount cash flows back to their present value will have a significant impact on the net present value of the contingent value right.

There are two forms of discount rates that address the different types of risk associated with a contingent value right:

-

the risk of realizing certain financial metrics

-

the credit risk associated with the non-payment of the contingent value rights by the acquirer

For this reason, it is important to isolate risk into separate input components and avoid integrating any future risk associated with the probability or expected term of a milestone payment into the discount rate.

IV. Forecasted Financial Metrics

For those contingent value rights based on financial performance, the forecasted financial metric is a critical input. The accuracy of the forecast can impact the underlying risk inherent in the expected payout. In addition, the structure of the payout can impact how to most appropriately account for that risk. The forecasted financial metric will play a large role in what value is ultimately calculated.

Mechanics of Contingent Value Calculations:

The complexity of the valuation model related to contingent value calculations may be entirely different between the buyers of these companies issuing contingent value rights and holders (e.g. the fund investors), who maintain contingent value instruments in their investment portfolios. The most appropriate valuation methodology can vary depending on the structure of the payout and the risk profile of the issuer. For example, for issuers (e.g. an acquiring company), contingent value rights represent real liabilities on their balance sheet that may be subjected to a higher degree of scrutiny by regulators, auditors and stakeholders.

While the actual mechanics of the contingent valuation rights calculation are fairly straightforward, the outcome can have important implications for fund investors. Below, we highlight an example of a contingent value right and the approach towards valuation.

More details to these methodologies and detailed numerical examples exist in The Appraisal Foundation’s VFR 4.

Fund investor Considerations

From a fund investor’s perspective, contingent value instruments present several challenges that must be carefully scrutinized and monitored on a recurring basis. Several factors can be leveraged by fund investors to pre-empt concerns and avoid lengthy discussions with their auditors that, in turn, can impede the timely issuance of year-end financial statements.

I. Subjectivity

While we addressed the highly subjective nature of deriving probability weightings, it is critical that the fund investor maintain and document a rationale for applying certain probability weightings within its valuation policy. Even if qualitative in nature, the fund investors’ outlined framework for an approach to probability weightings will help provide some high-level consistency.

For example, in the case of biotech contingent value rights, it is recommended that studies of historical regulatory approval rates for the specific drug therapy types be considered as part of the probability of success assessment and determination. While these past approval rates might not represent the actual probability weightings, they provide useful insights for fund investors and their conclusion.

In addition, as a litmus test against their own valuation conclusions, some of the publicly traded acquirers issuing contingent valuation rights provide can provide fund investors an in-depth analysis of the the liabilities within their financial statements, including discussions of the major inputs. While fund investors cannot rely on the issuer’s calculations for their own current valuations, they can provide a reasonable data point for their assumptions and reasonableness on a recurring basis.

II. Materiality/Immateriality

While reviewing contingent value instruments, the fund investor should pay close attention to the potential impact on the financial statements. The realization of a contingent value milestone may prompt these instruments to shift to a material position within the financial statements. Conversely, while not implicit, if a milestone were subsequently triggered following the issuance of financial statements, a misstatement could occur.

It is incumbent upon the fund investor to maintain a steady dialogue to monitor contingent value thresholds in order to pre-empt any problem regarding materiality that may surface either during the course of the audit or thereafter. It is also recommended that a risk matrix be created to capture the potential impact, likelihood and timing of various milestones embedded in any contingent value instruments held in the investment portfolio.

III. Discount Rate vs. Probability Weightings

In assessing the discount rate in a contingent value calculation, the fund investor must clearly distinguish between the actual discount rate from the probability of certain milestones materializing. It is often the case that the fund investor itself adjust the level of the discount rate to account for the likelihood of a future contingency occurring. This is an incorrect approach. As discussed, the discount rate should capture the risk associated with the underlying forecasted financial metrics as well as the risk of non-payment.

So, in evaluating an appropriate discount rate, the fund investor must clearly bifurcate between the appropriateness of the discount rate itself and the probability of a milestone or event occurring. A reasonable assumption following the alternative use of capital invested in contingent value should be apparent in the valuation consideration.

IV. Unique Complexities: Each Contingent Value Instrument is Different

In assessing the risk and potential materiality of contingent value, the fund investor must acknowledge that each contingent value instrument is unique in complexity and sophistication. As previously mentioned, in the case of most biotechnology deals, contingent value rights are often binary in outcome. However, in many technology related transactions, earnouts that are not. In the latter, it is often the case that hitting a degree of success will result in a pro-rata percentage of an earnout.

To fully understand the potential impact on materiality, the fund investor must not only monitor triggers imbedded in the contingent value instruments but also distinguish and categorize the differences between various contingent value instruments to properly assess and capture their impact. Once again, a risk matrix is recommended to measure the degree of impact as well as the potential timing of the payment.

Conclusion

As the notion of contingent value continues to gain traction to bridge value gaps between buyers and sellers, fund investors must develop a framework to monitor and gauge this highly volatile Level III fair value measurement.

A carte blanche assessment of all contingent value instruments cannot properly capture the impact on materiality and the impact on the financial statements and net asset value of the fund. An attempt to do so may well result in a misstatement causing the fund investor undue time and incremental expense, in the context of the year-end audit.

SHARE