Nonprofit Standard Newsletter - Winter 2020

Table of Contents

- Thank you, Dick!

- What is the Private Nonprofit Sector Going to Look Like in the New Post-COVID Environment?

- Questions Audit Committees Should Consider In The Current Environment

- Federal Funding Terms Demystified

- Directors & Officers Liability Insurance for Nonprofits: What You Need to Know About But Were Afraid to Ask

- How Nonprofits can Protect their Data and Reputation in the New Era of Data Privacy

- Other Items to Note

Thank you, Dick!

This article recognizes and thanks Dick Larkin for his many years of service both to BDO and the entire nonprofit industry.

Dick has served the nonprofit industry for over 50 years. Over this time he has been widely considered to be one of the premier experts in accounting and auditing issues for nonprofit organizations. Over his years of service he contributed extensively to the creation and interpretation of nonprofit financial accounting, reporting and auditing standards. He has been an invaluable resource to the nonprofit industry throughout his career.

Dick has been a Technical Director in the Nonprofit & Government practice of BDO for over 20 years. Prior to joining BDO, Dick spent the first 31 years of his professional career at PricewaterhouseCoopers with most of his time in the national office as a technical director in the Not-for-Profit Industry Services Group. In his role as a technical director throughout his career, he has provided thought leadership to the nonprofit industry and assisted firm partners and staff worldwide with accounting and auditing issues involving nonprofit organizations.

Dick has not only served the nonprofit industry through his independent accountant role as a member of professional firms, he has tirelessly served the nonprofit industry by serving as a member of numerous nonprofits as a board member, treasurer and consultant.

Dick has authored numerous books and articles tackling many different topics affecting the nonprofit industry. Included in the long list of books he has authored or co-authored that are essential tools for both public accountants as well as industry professionals are Not‑for‑Profit GAAP and Financial and Accounting Guide for Not-for-Profit Organizations.

Dick has been active in many professional and industry organizations throughout his career. He has been a member of the AICPA’s Not-for-Profit Organizations Committee, Not-for-Profit Display Issues Task Force and Not-for-Profit Audit Guide Revision Tax Force at various times over his career. He also served on the Financial Accounting Standards Board Not-for-Profit Advisory Task Force.

In recognition of his continual commitment and leadership in the nonprofit industry Dick has received Lifetime Achievement Awards from both the AICPA and the Greater Washington Society of CPAs.

Dick has also served as an adjunct professor of not-for-profit management at Georgetown University and, as a Peace Corps member, he taught business administration at Haile Selassie-I University in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

Dick was a longtime member of the Cathedral Choral Society and contributed his musical talents at many events at the Washington Cathedral. Dick is also an avid world traveler and stamp collector.

It is with immense gratitude that we wish Dick a sincere thank you for all his years of service, both to BDO and the nonprofit industry as a whole. His guidance has been pivotal in developing the quality of standards we have today. His wealth of knowledge cannot be replaced and we are extremely grateful for his nonprofit industry commitment and leadership.

“ Dick is a legend in the not-for-profit world. If you ever need an answer, go to Dick. Nobody knows not-for-profit GAAP better than Dick. He has this uncanny knack of being able to take the most complex situation and make it seem so simple. ” -Wayne Berson, Chief Executive Officer

“ Dick is an invaluable member of BDO’s Institute for Nonprofit ExcellenceSM. His sage advice has helped innumerable BDO clients and engagement teams come to the right conclusions on technical accounting matters. ”- Christopher Tower, National Assurance Managing Partner

“ Dick Larkin set the standard for excellence in the nonprofit accounting field. Dick, along with Wayne Berson, created our BDO Institute for Nonprofit ExcellenceSM, the first one in the public accounting industry. When we created our blog in 2012, we wanted to pay homage to Dick’s contributions by naming it the Nonprofit Standard, setting the standard in the industry. ” - Adam Cole, Partner and National Co-Leader, Nonprofit & Education Practice

“ I’ve had the privilege of working with Dick for nearly 20 years and, in that time, I have valued his deep technical knowledge combined with a practical perspective built on his broad and varied industry experience. Known as “Mr. Nonprofit” in industry circles, he has helped the management and boards of countless not-for-profit organizations tell their story through their financial statements. ”

- Laurie De Armond, Greater Washington D.C. Assurance Office Managing Partner and Executive Director, BDO Institute for Nonprofit ExcellenceSM

“ Dick has been a resource to me throughout my entire career. He has always been a voice of reason and a recognized expert to turn to for assistance with technical issues and accounting and auditing challenges. His depth of understanding of all things nonprofit and his ability to explain the standards has been a resource I have been truly thankful to have throughout the years. ” - Tammy Ricciardella, National Assurance Director, Nonprofit

What is the Private Nonprofit Sector Going to Look Like in the New Post-COVID Environment?

By Dick Larkin, CPA, MBA

This article summarizes some of the specific effects the nonprofit sector is experiencing such as remote work environments, remote learning, absence of large gatherings, less travel and the like.

As just one example, the absence of large gatherings and less travel translates into major disruptions of the ability of trade and professional associations to hold their normal conferences and conventions, which besides the structured educational components, also serve as networking opportunities for members, and as net revenue generators for the associations.

This article specifically discusses only private nonprofit organizations—other than healthcare, but some other organizations can look here for examples of similar concerns. Governmental educational institutions have many of the same issues as private institutions. Healthcare organizations have some of the same concerns about fundraising, governance and general management, and investment management as do other organizations.

Of course there is much overlap among the areas detailed in the article. Most educational organizations and public-centered organizations also depend heavily on fundraising, many charitable and cultural organizations have members, many member-centered organizations have charitable affiliates, etc.

Overarching issues for the NONPROFIT sector

Effects on general organization operations and financial reporting

-

Management must make adjustments in internal procedures and oversight—especially when staff (paid and volunteer) may be working remotely—to ensure that organization functions are being carried out as intended. There will most likely be additional costs involved, which may be partly offset by savings on rental of office space no longer needed.

-

Management must keep governing boards informed about the effects of the virus on the organization and its constituents.

-

Maintaining financial liquidity, including an available line of credit, to be prepared for the unexpected (and the expected) is more important than ever. This sometimes requires management to judge between competing priorities: Should we spend now in response to the immediate crisis, or keep more in reserve for the future crisis we know is coming? Merging with another nonprofit organization might be considered. Even if the organization is financially healthy at the moment, there should be a Plan B and C, especially if the organization is greatly dependent on one or a few sources of support.

-

In-person activities such as on-site office work, meetings, performances, social events and some programmatic activities such as soup kitchens may necessitate medical testing of participants, which is costly.

-

Extra consideration must be given to possible impairment of assets like non-publicly traded securities, non-financial assets such as inventory, real estate (e.g., owned rental property which is now (or soon to be) vacant because the tenant went out of business or may be about to), deferred charges and goodwill. The allowance for uncollectible receivables—especially pledges—is always a sensitive area; it is more so now.

-

Organizations conducting any group activities—even with appropriate precautions—should have insurance in place to cover liability for defense and payment of claims that infections occurred in connection with these activities.

Effects on fundraising

-

Donors of all types are themselves often in strained financial circumstances due to loss of jobs or reduced work hours (individuals), reduced tax revenue (governments), reduced profits (businesses) or reduced investment income (foundations). This may limit their ability and willingness to give. (Many organizations have initially seen an increase in fundraising efforts but time will tell if this is prolonged.)

-

The elimination for 2020 of the required minimum distribution from IRAs held by those over age 70½; (will that be repeated in the future?) has removed one incentive to giving by these people.

-

Management must maintain open communication with current and prospective donors about the effects of the virus on the organization and how management is dealing with them.

-

If unspent restricted gifts on hand were given for activities that now have a lower priority or those that cannot be carried out in the current environment, maybe the donors would agree to re-purpose their gifts for now-higher priority activities or for unrestricted purposes.

Effects from limitations on travel

-

Organizations that do hold meetings will likely see reduced attendance. (See the related points below under educational and member-centered organizations.)

-

Organizations should look at event insurance to determine if they have the appropriate insurance in case of future cancellations and what is covered in the policy.

-

Technology improvements may be needed to offer meetings and other events virtually.

Effects related to remote work and learning

-

Additional internal controls and management oversight will be needed to assure compliance with proper procedures, especially when staff size is limited.

-

Additional technology issues will need to be addressed, and related costs incurred. (See effects related to technology section below.)

-

Auditors will have additional challenges in documenting and evaluating the design and effectiveness of internal controls.

-

Volatility in investment markets will require additional attention by management and governing boards to monitor investment portfolio performance and oversee outside investment managers.

Effects related to technology

-

Virtual activities such as classroom teaching, musical performances and office operations will require specialized technology to be acquired and operated, with technical support readily available in real time to deal with the inevitable problems. Additional costs will be incurred.

-

Increase in technology resources to ensure the entity is protected against cybersecurity attacks has become essential with the remote working environment.

Effects on specific types of organizations

Effects on charitable organizations and others that depend heavily on donated support

-

Social service organizations such as food banks, soup kitchens, counseling services, charity clinics, etc. are seeing increased public needs by those who have suffered reduced personal income and/or increased personal stress, together with a need to maintain social distancing, engage in additional sanitizing and enforce mask requirements with clients.

-

At the same time, fundraising may be more challenging as noted previously. The additional effort required to obtain needed resources will likely result in a higher ratio of fundraising expenses to contributions raised and a lower ratio of program expenses to total expenses. These ratios are looked to by many—rightly or wrongly—as meaningful indicators of an organization’s ‘worthiness’ as a recipient of charitable gifts. Organizations must be able to explain their ratios to donors and to the public.

-

Grantmaking organizations that rely on their endowment to generate the cash to make grants must continue to be prepared for greater volatility in investment markets, and a potential reduction in investment returns. They should be cautious about making long-term funding commitments without having certainly available cash. At the same time, they are likely to receive additional requests for funding by other nonprofit organizations which are themselves experiencing financial stress.

Effects on educational organizations

-

Remote learning will require additional resources devoted to the required technology, training and support of teachers and students.

-

Students might decide not to re-enroll next year. Some may just take a year off; others may never come back.

-

Some residential institutions may find themselves with underutilized housing and dining facilities, and all institutions with underutilized meeting facilities, which still must be maintained.

-

Limitations on travel will affect the ability of students from foreign countries, and in some cases even from other states, to attend in person, ability of students to study abroad, ability of faculty and students to attend educational conferences or collaborate in research with colleagues at other institutions, and of athletic teams to travel to games.

-

In-person group activities such as classes, meetings and athletic events may be limited to only the permitted number of attendees/participants, require re-configuring of meeting spaces, require additional medical testing, and facilities for sequestering persons who test positive.

-

Sports, by their nature of close personal contact, heavy breathing and travel to game locations, requires special care to ensure safety of athletes, coaches, staff and fans (if allowed).

-

Educational institutions have to answer to a larger variety of constituencies than most nonprofits. Besides students, there are parents, faculty, staff, donors, alumni, regulators and residents of the town where the institution is located, all of whom have—sometimes competing—agendas. For example, after a period of remote classes, students may want to return to campus sooner than the faculty or community want them to.

-

On-campus student organizations, such as academic and social clubs, performing arts groups and service organizations will likely be constrained as to how, when and where they can be active.

Effects on member-centered organizations

-

Increased unemployment and business failures will reduce the ability and willingness of members to join the organizations, advertise in the organizations’ publications, and participate in meetings and other programmatic activities of associations and clubs.

-

Charitable and educational affiliates of such organizations will be subject to the same issues as discussed under those headings above.

Effects on public-centered organizations

-

Visual arts organizations are having to deal with limitations on their activities, such as availability of non-owned venues, permission by local governmental authorities to hold live in-person events, willingness of visitors to attend exhibitions and the ability to enforce protective measures, such as limitations on numbers of visitors, use of masks, sanitizing and social distancing.

-

Performing arts organizations have the same issues as visual arts organizations, plus willingness of performers to gather for rehearsals and performances, and of audiences to attend.

-

Cultural organizations may be limited in their ability to bring performers from other countries or make foreign tours.

-

If they plan to have virtual exhibits/performances, the specialized technology involved will have to be acquired and operated. A decision needs to be made about how to charge ‘attendees’ of virtual events: the same as for live events, reduced charge, free. Also, since the experience by attendees at such events is not the same as at live events, participation may be lower, which may also lead to a reduction in contributions.

-

If in-person events are limited or canceled, besides less revenue from admissions or ticket sales, there will be a reduction of revenue from sales by the organizations’ on-site gift shops. This might be partly made up with online sales.

Effects on religious organizations

Note: “Religious organizations” is a very diverse group, including all the above types and considerations discussed previously.

-

Organizations that send missionaries to foreign countries may have limited ability to do so.

-

The unique aspect here is group worship and other services that may be limited or prohibited as well as carrying a high risk of spreading the virus if they are even being conducted.

Management and those charged with governance, as well as committees they may have established to address these issues, need to be involved and monitoring these and other issues on an almost daily basis. The ability to adapt to this ever-changing environment and the needs of your stakeholders is critical to the ability of your organization to not only survive these times but to thrive in the current environment and in the future. The organization should consider posting regular updates on the status and effect of COVID-19 on their websites and make them available to stakeholders. Communication is critical to managing these risks and answering the questions of your stakeholders.

For more information, contact Dick Larkin, assurance director, at [email protected].

Questions Audit Committees Should Consider In The Current Environment

Audit-Specific Questions

-

What unintended consequences of COVID-19 may increase incentives or pressures on management that may result in management override of controls?

-

Are we able to ensure continued proper segregation of duties and monitoring controls given changing physical work situations?

-

Have any significant risks or material weaknesses been identified as a result of impacts from COVID-19?

-

What changes in risk assessments have auditors determined need to be made and how will that impact the audit strategy?

-

Are there known impediments—either by management or by the auditors—that may delay timely filing of financial statements? (e.g., lack of access or ability to obtain audit evidence or other information)

-

What additional resources or expertise may be needed by management to properly account for judgments or estimates or changes related to circumstances brought on by COVID-19?

-

What additional efforts may be required by the auditor to ensure the performance of a high-quality audit?

-

Does my audit firm have the depth of or access to resources adequate to address complex accounting and auditing questions, including industry-specific matters, as they arise?

-

Do my management teams, as well as my auditors, have the ability to properly supervise and direct the work of their staff and teams?

-

Are there additional challenges in performing auditing procedures due to multi-geographical considerations?

-

Has COVID-19 impacted circumstances that may call into question the entity’s ability to continue as a going concern? What are management’s plans to address? How do these impact the auditor’s going concern evaluation?

-

Are there any auditor independence issues that have arisen with respect to COVID-19?

Accounting and Reporting-Specific Questions

-

Has management adequately assessed changes in risk factors impacting our business? Are these appropriately reflected in our financial statements?

-

Has management properly identified significant accounting areas where impacts from COVID-19 are likely? Has management further accounted for related income tax effects of these impacts?

-

Have we properly accounted for and disclosed changes in significant estimates and judgments impacting the financial statements?

-

Has management, along with the auditors, identified applicable relief opportunities with respect to the 2020 CARES Act and appropriately factored these into the accounting and reporting, including income tax effects, within the financial statements?

-

Do we have a requirement to comply with the Yellow Book and/or the Uniform Guidance related to any coronavirus relief stimulus funding that may have been received?

-

Are there accounting or disclosure matters that have required significant consultations outside of the audit engagement team?

-

Have the auditors and management identified significant or industry-specific matters related to the interaction of the CARES Act and GAAP or GAAS impacting our financial statements that need regulatory consultation?

-

Has new information arisen regarding COVID-19 events contained in previously filed financial information that requires updating of current disclosures?

Corporate Governance-Specific Questions

-

As an audit committee, how are we maintaining our education with respect to COVID-19 considerations, relief efforts, and related risks and opportunities?

-

Are we appropriately engaging with internal and external stakeholders and providing transparent and consistent communications about significant impacts on our business?

-

Are we allocating enough time and making ourselves available to discuss critical issues as they arise with management, the auditors and the board?

-

Are we keeping the full board appropriately updated as to significant challenges with respect to financial accounting and reporting?

-

Are we considering responses to anticipated questions from board members during upcoming annual meetings?

-

Is management actively and effectively engaging with lenders, members and other stakeholders in a timely and productive manner and are the results of those engagements reflected in the financial accounting and reporting?

-

Are we, as a board committee, appropriately considering additional risks that have arisen related to other stated committee responsibilities as described in our Audit Committee Charter—e.g., COVID-19 cybersecurity and data privacy risks?

Federal Funding Terms Demystified

By Barbara Finke, CPA

Reading through the copious articles and opinions on what this audit could entail, you may see terms such as Yellow Book Standards, Uniform Guidance or Single Audits, which may or may not be defined, as they are commonly known among entities that have historically received funding from governmental agencies.

This article will help define these concepts for entities new to federal funding.

Yellow Book

It wasn’t that long ago that standards were printed, bound and available on each accountant’s bookshelf. In order to make it easier to know which book to grab when researching audit standards or policies written by the U.S. Governmental Accountability Office (GAO), each book was color coded. Although these books are all available online now, the GAO kept the well-known color coding system and these reference guides are now commonly referred to by the color of the “binding.” The most commonly used books related to the GAO’s role as an audit institution are the Yellow and Green Books.

The publication of Government Auditing Standards is commonly referred to as the Yellow Book. Per the GAO, the Yellow Book is “used by auditors of government entities, entities that receive government awards and other audit organizations performing Yellow Book audits. It outlines the requirements for audit reports, professional qualifications for auditors and audit organization quality control. Auditors of federal, state and local government programs use these standards to perform their audits and produce their reports.” The Yellow Book was updated in 2018, and those updates will be effective for financial statement audit, attestation engagements and reviews of financial statements for periods ended on or after June 30, 2020 or performance audits that began on or after July 1, 2019.

When a CPA states that the audit will be performed under the Yellow Book standards, it means that the audit will be conducted under both Generally Accepted Auditing Standards (GAAS) and also Generally Accepted Governmental Auditing Standards (GAGAS). The Yellow Book is meant to enhance the accountability for use of government funds by any entity. Therefore, any type of company (public/private, not-for-profit, for-profit, governmental, etc.) in any industry could be subject to the Yellow Book requirements if the funding agency either requests the audit, or if local, state or federal regulations require the audit based on the level of funding spent (or received) by the entity.

The standard independent audit of financial statements is expanded from an audit under GAAS (or the standards of the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB) if the entity is a public company subject to SEC regulations) to include a report on internal control over financial reporting and on compliance with provisions of laws, regulations, contracts and grant agreement that have a material effect on the financial statements (Yellow Book Report). The auditor will focus time on ensuring that the entity has complied with material factors related to the public funding and will be considering whether any internal control deficiencies may result in waste or abuse related to public funds.

To determine if the funds that the entity received under the CARES Act or another relief fund will require an engagement utilizing the standards in the Yellow Book requires an understanding of the terms and conditions in the granting/contract documents and may require consultation with the funding agency directly.

Uniform Guidance or Single Audit

On Oct. 19, 1984, Congress passed the Single Audit Act of 1984. The original legislation required state and local governments and Indian Tribes expending more than $100,000 in federal funds to obtain a “single audit” by an independent auditor.

The Single Audit was the term coined for the new approach meant to create more effective and efficient oversight of the use of public funds, specifically federal funds spent. Instead of separate audits of each program and separate financial versus compliance audits, a “single audit” would be conducted that looked at the organization (not grant by grant) and combined compliance and financial elements.

The Single Audit Act regulations are managed by the Federal Office of Management and Budget (OMB). In order to assist both auditors and non-federal entities in understanding the requirements for auditing and managing federal funds, the OMB issued several circulars subsequent to the Single Audit Act of 1984:

-

A-21 Cost Principles for Educational Institutions

-

A-87 Cost Principles for State, Local and Indian Tribal Governments

-

A-110 Uniform Administrative Requirements for Grants and Other Agreements with Institutions of Higher Education, Hospitals and Other Non-Profit Organizations

-

A-122 Cost Principles for Non-Profit Organizations

-

A-89 Catalog of Federal Domestic Assistance

-

A-102 Grants and Cooperative Agreements With State and Local Governments

-

A-133 Audits of States, Local Governments and Non-Profit Organizations (Circular A-133)

-

A-50 Audit Follow-up

In 1990, with OMB Circular A-133, OMB added not-for-profits to the list of entities required to obtain Single Audits if the entity expenditures met the threshold.

In 1996, Congress passed an amendment to the Single Audit Act of 1984, designed to improve the effectiveness of single audits. This amendment increased the expenditure rate of federal funds requiring an audit and introduced a risk-based audit approach, and gave the OMB the flexibility to make future single audit changes as needed.

In 2013, the federal government, in connection with other agencies, issued Uniform Administrative Requirements, Cost Principles and Audit Requirements for Federal Awards commonly referred to as the Uniform Guidance. This new guidance, issued at Chapter 2 of the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR), Section 200 (2 CFR 200), combined the multiple previous sources of guidance related to the Single Audit Act and the Circulars into one central location, and to amended the information to further enhance the effectiveness and efficiency for both auditors and non-federal entities. The thresholds for entities requiring audits also increased to $750,000 in expenditures of federal funds. The Uniform Guidance is applicable to any funding issued after 2014, and audits conducted for periods ending on or after June 30, 2016.

The Uniform Guidance is organized into several parts:

-

Subpart A—Acronyms and Definitions

-

Subpart B—General Provisions

-

Subpart C—Pre-Federal Award Requirements and Contents of Federal Awards

-

Subpart D—Post-Federal Award Requirements

-

Subpart E—Cost Principles

-

Subpart F—Audit Requirements

Audits conducted under Subpart F of the Uniform Guidance are often still referred to as Single Audits. These audits entail an in-depth look at selected major programs operated by the non-federal entities including financial and compliance factors. Every year OMB issues a Compliance Supplement that provides guidance as to what compliance factors are relevant for audit procedures, provides guidance to the non-federal entity and the auditors on how those compliance factors should be complied with, and how the compliance should be tested. Furthermore, Subpart F requires that all audits in accordance with the Uniform Guidance must also be conducted in accordance with the Yellow Book requirements. Therefore, if your entity will be obtaining an audit under Uniform Guidance, the audit will also be conducted under the Yellow Book standards. An audit under Subpart F will include the reports required by GAAS or PCAOB, the Yellow Book Report, an independent auditor’s report on compliance for each major program, and a report on internal control over compliance.

The Uniform Guidance generally applies to all non-federal entities receiving funds from federal agencies (see 2 CFR 200.101 for certain scope exceptions). A non-federal entity is defined by the Uniform Guidance as “a state, local government, Indian tribe, institution of higher education, or nonprofit organization that carries out a federal award as a recipient or subrecipient”. However, 2 CFR 200.101(c) states that a federal agency can make Subparts A-E of the Uniform Guidance applicable to “for-profit entities, foreign public entities, or foreign organizations, except where the federal awarding agency determines that the application of these subparts would be inconsistent with the international obligations of the United States or the statutes or regulations of a foreign government.”

The definition of a non-federal entity does not encompass for-profit entities, and therefore many entities may wonder about why an article such as this is important for any entity receiving CARES Act funds to review. Under Subpart F of the Uniform Guidance, there is a note that a federal agency or a pass-through funding agency can add the Single Audit requirement through the grant’s terms and conditions to a for-profit. The CARES Act provided over $2 trillion in economic relief, including billions to for-profit entities through federal agencies. In reviewing the history of the Single Audit and the goal to ensure that government funds are given efficient and effective oversight through external audits, it is not surprising that many federal agencies have included the Uniform Guidance requirements as part of the terms and conditions for the use of the CARES Act funds.

Green Book

The Green Book is the Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government. Per the GAO, the Green Book could be used by someone who manages programs for federal, state or local governments; someone conducting a performance audit or a financial audit; or someone responsible for making sure that the personnel follow policies and procedures related to any and all job responsibilities related to government funding controls.

The Green Book organizes internal control into five components 1) Control Environment, 2) Risk Assessment, 3) Control Activities, 4) Information and Communication and 5) Monitoring. Each component is made up of separate control principles which detail certain control attributes that combined help to provide a cohesive system of internal controls.

The Uniform Guidance notes that non-federal entities establish and maintain internal control over the federal awards that provides reasonable assurance that the non-federal entity is managing the federal awards in compliance with federal statutes, regulations, and the terms and conditions of the federal awards. The guidance notes that the internal controls established “should” be in compliance with the Green Book or the “Internal Control Integrated Framework (revised in 2013), issued by the Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission” (COSO). The use of the term “should” indicates that this is not required, but is considered to be a best practice and, therefore, entities would want to review the Green Book or COSO in their entirety to help ensure that an adequate system of internal control is designed and maintained. Part 6 of the yearly OMB Compliance Supplement helps auditors and non-federal entities by providing illustrative controls for each type of compliance requirement and is another good tool to help understand the practical application of the Green Book standards.

In summary, the federal government strives to maintain a process whereby the use of government funds is effectively and efficiently monitored to limit waste, fraud or abuse. When you receive any funds from the federal government, it is imperative to carefully read the terms and conditions of the grant agreement, utilize the beta.sam.gov website to obtain information on the funding and speak with the funding agency to understand the audit requirements that will be expected. It is critical to maintain detailed records of how the funds are spent or amounts charged to federal awards were in compliance with the agreement. Even if the entity is not ultimately required to have an audit in accordance with the Yellow Book or the Single Audit, it is responsible for complying with all requirements and maintaining appropriate documentation.

For more information, contact Barbara Finke, assurance director, at [email protected].

Directors & Officers Liability Insurance for Nonprofits: What You Need to Know About But Were Afraid to Ask

By Paul E. Hammerschmidt, CPA, (MS Taxation) of BDO USA, LLP and

William J. Zester, Executive VP, Commercial Lines of Pavese-McCormick Agency, Inc.

In our experience, nonprofit organizations sometimes pay more attention to the philanthropic cause, grant making and donors than to the “business” side of the organization. A seasoned leadership team will understand the value of D&O insurance. Any prospective board member should not join a nonprofit board without verifying coverage under a D&O policy. Nonprofits that want to attract talented board members would be wise to consider maintaining a robust D&O policy.

Claims under D&O policies typically originate from:

-

Failure to comply with workplace laws (including harassment, discrimination and wrongful termination)

-

Breach of fiduciary duty

-

Lack of corporate governance

Typical Exclusions of a D&O policy:

-

Bodily injury, sickness, humiliation, mental anguish, emotional distress, assault, battery, disease or death

-

Damage to or destruction of any tangible property and/or resulting in loss of use

-

Fraud and criminal offenses

-

Lawsuits between directors and officers within the entity (this prevents collusion against the insurance company)

The organization applying for D&O liability insurance should be aware that if they fail to disclose material information or willfully provide inaccurate information, the insurer may seek to avoid payment due to misrepresentation. Thus, the application is made part of the policy.

Since D&O policies are not issued on standard forms, they vary from insurer to insurer, state to state, and contain many options as to coverage, limits and costs. We will highlight some of the more common options and coverages; however, the recommendation is always to secure the advice of a professional licensed independent insurance broker to assist with this process.

Typical Elements of a D&O Policy:

Claims Made Policy

In almost all cases D&O policies are “claims made” and not “occurrence” policies. The claims “trigger” is the date when the claim is presented to the insurance company under the policy currently in effect. The action causing the claim must have happened after the “inception date” of the policy in force or “retroactive date” listed on the policy prior to the inception date. Therefore, it’s important to discuss with your insurance broker any potential claims, change in insurers, bankruptcies or policy cancellations. These events can leave an organization without coverage if not handled appropriately.

“Tail coverage” or “extended reporting period” helps to extend the reporting period of a claim beyond the cancellation of a policy for a defined period at an additional cost.

Policy Form

Limits of coverage can be chosen from $1 million and well beyond depending on the size of the organization, contract requirements or financial considerations.

Retention (deductible) options can be offered at some premium savings. However, if an organization has experienced claims issues, oftentimes the insurer will require increased retentions to avoid paying on smaller frequency claims.

An organization’s subsidiary (i.e., at least 50% owned or controlled) or affiliate can often be added to the D&O coverage at inception or thereafter by including it in the application.

Duty to Defend vs. Duty to Indemnify

The term “duty to defend” essentially means that in the event a claim is made against an insured for an alleged wrongful act, the insurance carrier has the right and duty to defend the claim—even if the claim is groundless, false or fraudulent.

The insurance marketplace also offers “indemnity/reimbursement” or “non-duty-to-defend” coverage. This kind of policy provides that it’s the insured’s responsibility to defend a claim, subject to the insurance carrier’s written approval or consent.

An indemnity/reimbursement policy allows the organization to choose its own legal counsel, often from a list provided by the insurer that is sometimes referred to as a “panel counsel.” Most other policies allow the insured to select legal counsel, subject to the carrier’s consent. The carrier will then reimburse what they consider to be “reasonable” defense costs. The issue here is that the organization and carrier might not agree entirely on what they consider to be reasonable costs for a D&O defense claim.

If the policy states defense costs fall within the policy limits, this means that they will erode the total limit of liability available for claims payment. Therefore, it’s important to understand whether the policy includes defense coverage or if it’s outside the policy limits. The latter is usually a better option because the defense costs outside the limits don't erode the policy limits available to pay settlements resulting from a suit.

Coverage Endorsements

A “settlement cap provision” is an insurance policy clause permitting the insurer to compel the insured to settle a claim. The power is given to the insurer to force the insured to settle by placing a cap on the amount of indemnification they are willing to provide. For instance, the cap may be set at the amount the insurer believes the settlement is worth. If the insured refuses to settle, they could be held responsible for their own defense costs.

Settlement rights and obligations under a D&O policy provide that both parties must agree on any settlement offer. However, if the insurer wants to settle and the insured does not, a “hammer clause” in the policy would define a percentage the insured would pay of the difference between the settlement and final judgment. (e.g., 50/50 where the insured would pay 50% of the difference).

A “priority of payments provision” is found within most, but not all D&O policies that sets forth the order in which policy proceeds will be paid out to the various insureds under the policy (i.e., claims against directors and officers paid first before claims against the organization).

It’s good practice to “plan for the worst and hope for the best” so a “bankruptcy clause” is recommended, which directs the D&O policy to provide that the organization’s obligations are not relieved should the organization file bankruptcy. Insurer must still defend and make payment for its insured.

Virtually all D&O policies also include an “insured v. insured exclusion,” which precludes coverage for claims brought by or on behalf of or at the direction of any of the insureds (with some exceptions). One of the reasons for this exclusion is to prevent collusion between the entity (insured party) and an officer or director.

Employment Practices Liability Insurance (EPLI) is often offered as a separate insuring agreement to the D&O policy. It’s a coverage designed to protect employers from employee lawsuits alleging workplace-related wrongdoings.

Its importance cannot be underestimated, since most of the claims that are submitted are associated with this coverage. Employment-related lawsuits have taken an upswing in recent years and span a wide range of wrongful and improper acts. These may include sexual harassment, wrongful termination, discrimination based on a protected class, violation of the Americans with Disabilities Act, wage and hour violations, or whistleblowers provisions for retaliation against an employee for exercising the individual’s legal rights. These are a sampling of the hiring, firing and associated employment pitfalls that may ensnare your organization.

The Big Five Claims:

1. Improper hiring practices

2. Wrongful termination (including volunteers)

3. Hostile work environment/retaliation

4. Discrimination

5. Sexual harassment

It’s important to remember that not all lawsuits have merit, but even frivolous lawsuits need defense coverage and that’s also what you’re buying with a D&O policy.

It’s usually advisable to add “third-party coverage.” This feature expands the definition to include claimants other than employees of the organization. Third-party endorsements add vendors, clients and employment applicants as all of them can bring a lawsuit against the organization.

It is usually best to secure separate limits for an organization’s D&O and EPLI coverage. This separation prevents one claim from reducing limits across the policy.

Retentions (deductibles) are often higher on EPLI coverage than on a D&O policy.

In Conclusion

Directors & officers liability policies and employment practices liability insurance have come a long way from their beginnings. Coverage endorsements and exclusions are plentiful and can significantly change the protection offered by these policies. Care must be taken when canceling or switching policies. If an organization’s board members practice the three fiduciary responsibilities, namely the duty of care, the duty of loyalty and the duty of obedience, as mandated by state and common law along with lawful best practices guidelines for policy and procedure, they can avoid many of the common claims. The advantages are lower insurance costs and retentions.

Always consult a licensed and experienced independent insurance broker for advice and consultation when purchasing or changing an organization’s D&O insurance program.

For more information, contact Paul E. Hammerschmidt, tax director at [email protected] or William J. Zester, Executive VP, Commercial Lines who specializes in serving nonprofits at Pavese-McCormick Agency, Inc., an independent insurance agency at [email protected].

How Nonprofits can Protect their Data and Reputation in the New Era of Data Privacy

Karen A. Schuler, CIPP-US, CIPM, CDPSE

Consumer information privacy regulation laws are gaining traction across the country and will continue to become more prevalent and robust as more states adopt new legislation. There are currently several CCPA copycat laws being considered in other states including:

-

Nebraska Consumer Data Privacy Act (Legislative Bill 746)

-

Virginia Privacy Act (HB 473)

-

New York Privacy Act (Senate Bill 5642/A)

Although nonprofit organizations are typically exempt from consumer privacy regulation laws like the CPRA, their members, donors and staff still expect to have their personal information secured and protected. A nonprofit that experiences a ransomware attack or a data breach can still be impacted by data breach notification laws in addition to bad publicity and a loss of trust in their services. Nonprofits need to successfully know, protect and govern their data to create a data privacy protection plan.

Know your Data

Most nonprofit organizations entrust their data storage to third-party hosting providers and applications to minimize their in-house IT footprint. This may help cut costs, but it makes it challenging for nonprofits to answer key data privacy questions such as:

-

Who has access to our data?

-

Where does our data go (e.g., other vendors)?

-

How long is our data retained?

-

When does data get deleted?

When engaging third parties, nonprofits need to evaluate vendor contracts to ensure that they contain necessary data protection clauses regarding data storage, data management, data retention and destruction.

Vendor contracts should be evaluated to:

-

Ensure that they are current and can withstand the scrutiny of a regulator

-

Evaluate risk thresholds to ensure that the organization is protected if the vendor experiences a data breach

-

Review current insurance policies, such as cyber liability insurance, to determine whether ample protections are in place

Protect Your Data

Personal data, such as information on donors, members and recipients of services, is the lifeblood of a nonprofit, and protecting it should be a top priority. There has been a recent uptick in business email compromise attacks that have organizations of all sizes reconsidering their data protection tactics.

To create a comprehensive data protection program, an organization should consider:

-

Data classification schemas to understand where personal data resides and who has access to it

-

Incident response plans to ensure that there is a mechanism to respond if (and when) an incident or a breach occurs

-

Administrative and technical controls to ensure they are current and that patches are implemented at appropriate times

-

User policies and how data should be handled and monitored

Govern Your Data

Data governance helps an organization define who can do what with the data it stores by creating a set of processes, roles, policies and metrics to manage data. Data governance programs can increase the quality of data, eliminate redundancy and allow the nonprofit to make better decisions faster.

Data governance programs should include:

-

An executive-level champion that secures resources

-

A charter that outlines the purpose of the program and how it will be managed

-

A cross-functional committee that is assigned roles and responsibilities to deliver the program

-

A program manager that can help move tasks and initiatives forward

-

Funding to support initiatives

Steps to creating a data governance program include:

-

Identifying the locations of personal data

-

Determining which databases or sources contain the most valuable personal data (highest risk data)

-

Evaluating the accuracy, redundancy and relevance of these data sets

-

Remediating data sources that are outdated, redundant or provide no value to the organization or its stakeholders

-

Determining if appropriate data protection administrative and technical safeguards are in place

-

Developing a go-forward plan that allows for routine evaluations of the data that reduces the amount of unnecessary data that is retained for periods that are reasonable

Developing a data privacy protection plan can seem like a daunting task, but nonprofits that know, protect and govern their data are already on their way to meeting the demands of future data privacy laws.

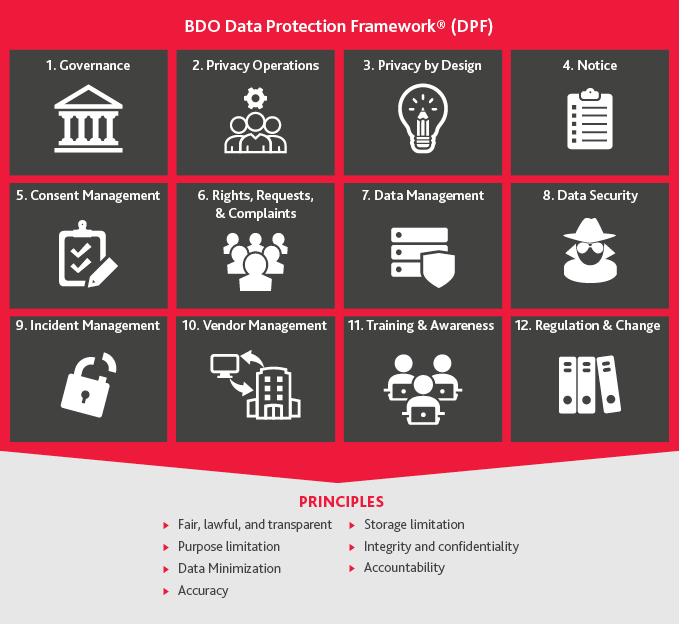

Build a Holistic Data Protection Program by using a Trusted Framework

BDO Digital has developed a data protection framework to help nonprofits build strong privacy programs that allow organizations to meet the needs of stakeholders, members and customers.

For more information, contact Karen Schuler, Practice Leader, Governance, Risk & Compliance, at [email protected].

Other Items to Note

Consolidation of a Not-for-Profit Entity by a For‑Profit Sponsor

On Oct. 21, the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) has added a narrow-scope project to its technical agenda to develop consolidation guidance to determine whether a for-profit sponsor should consolidate a nonprofit entity. Situations exist where a for-profit entity controls a nonprofit entity through sole corporate membership, ownership of a majority voting interest or other means, but for tax reasons the for-profit sponsor does not have a claim on assets transferred to the nonprofit entity. Currently the Accounting Standards Codification (ASC) does not address this scenario specifically.

Entities with this situation currently often analogize either to proposed consolidation guidance that was not finalized by FASB or to the aspects of ASC Subtopic 958-810, Not-for-Profit Entities—Consolidation. Using these two options has led to diversity in the consolidation determination.

The board will begin initial deliberations on the issue at a future meeting.

Current Status of a Single Audit for Major Relief Funds

A Single Audit encompasses a financial statement audit under the Government Auditing Standards and the Uniform Guidance.

Based on the current financial assistance listings at press time as listed on sam.beta.gov, the following is a summary of whether the major relief funds provided by the federal government as a result of the coronavirus pandemic are subject to the Single Audit requirements of Subpart F of the UG.

-

Paycheck Protection Program issued by the Small Business Administration: Not Subject to a Single Audit

-

Provider Relief Fund issued by Health and Human Services: Subject to a Single Audit

-

Coronavirus Relief Fund issued by Treasury: Subject to a Single Audit

-

Education Stabilization Fund issued by Department of Education: Subject to a Single Audit

For more information on these and other relief funds see the AICPA, Government Audit Quality Center website for the nonauthoritative Summary of Uniform Guidance (UG) Applicability for New COVID-19-Related Federal Programs.

SHARE