Nonprofit Heart, Business Mindset: Maximizing Good

All nonprofits want to do good.

Helping their constituents and driving impactful, positive change in communities is what propels their mission forward. Whether they’re on a quest to combat social injustice, poverty or climate change, nonprofits play a vital role in keeping our society moving forward.

Nevertheless, while the desire to do good is laudable, it’s not enough. Nonprofits may have the best intentions in the world, but if they don’t learn how to maximize that good, they won’t be effective. Noble-sounding programs may appear great on paper, but organizations have a responsibility to ensure that they’re actually fulfilling their intended goals and evolving in a way that moves their mission forward.

What’s the formula for a strong, sustainable nonprofit?

Put simply, balancing a nonprofit heart with a business mindset.

So, how can nonprofits successfully maximize good? The answer can be borrowed from a classic adage:

“Charity begins at home.”

Just as a doctor cannot take care of others if he himself is ill, organizations cannot help their constituents if they’re unable to manage their own operations effectively and sustainably. As mentioned in our first insight, “The Business of Impact,” nonprofits must balance good intentions with a business mindset.

To maximize the good they do externally, they must make sure their own infrastructure is solid, and set up to evolve with the times.

This begins with learning how to balance external and internal needs. Too often, nonprofits, in a quest to save the world, fail to save themselves. They fall into the “starvation cycle”—a phenomenon in which organizations dig themselves into the red by prioritizing high programmatic spending over fundamental operational investments.

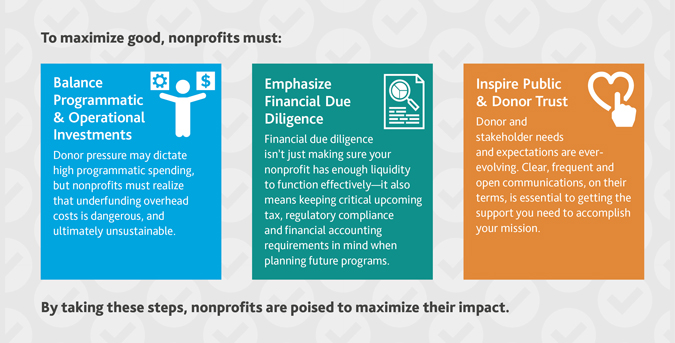

Balance Programmatic & Operational Investments

Nonprofit programs and activities are foundational to an organization’s work—they drive the mission forward, inspire new and ongoing donor support and increase public awareness of both the issue at hand and the organization. Strategic investments in updating or expanding a nonprofit’s programs are necessary to increasing impact.

Nevertheless, while investing heavily in programmatic work is important, it can’t be the only investment nonprofits are making. Failing to fund other necessary costs can lead nonprofits to spiral into the “starvation cycle,” from which there is no easy return.

Avoiding the Starvation Cycle

According to Nonprofit Standards, our benchmarking survey, 72 percent of nonprofit organizations spend 80 to 100 percent of their total expenditures on program-related activities—a metric many nonprofit watchdogs use to determine financial efficiency. This aligns with Charity Navigator’s findings that 7 in 10 nonprofits spend at least 75 percent of their budget on programs and services. About 1 in 5 (19 percent) spend an even greater amount—between 90 to 99 percent on program-related expenses.

At first glance, this high programmatic spending may look like a good thing. After all, the overhead myth—the dangerous assumption that low overhead costs are a good measure of a nonprofit’s performance—is quite pervasive among donors and supporters. Unfortunately, this has also contributed to the popularity of restricted donations, under the belief that a donor’s money would be more impactful if spent on direct costs tied to a nonprofit’s work.

The truth is, more isn’t always better. The “right” level of spending varies greatly by organization type. Falling on either end of the spectrum—underfunding or over-allocating—can be causes for concern. High programmatic spending may look favorable to outside observers, but it also likely means that organizations are underfunding the infrastructure—such as new technology, employee training and fundraising expenses—they need to sustain themselves long term. Too often, nonprofits strive to maintain their programs while starving their own organizations in the process.

Making Strategic Spending Choices

With this in mind, how can nonprofits make strategic spending choices that will strengthen themselves long-term?

Based on the IRS’ instructions to the Form 990, a nonprofit’s costs fall into three categories: Program Services, Management & General and Fundraising. The latter two are often referred to as “overhead” or supporting services. Although not directly related to programs, they are critically important to fund.

Below, we break down example categories of spending in each.

Management and General Costs

These are the costs needed to operate the organization, across all programs. Examples include:

Talent Management

From the Board and Executive Director to employees and volunteers, nonprofits need to support the people behind their mission and invest in recruiting and retention. Leading employee satisfaction issues, according to Nonprofit Standards, include compensation (considered by 78 percent to be a high or moderate-level challenge), up-to-date technology (48 percent), inflexible work schedules (34 percent), management-employee relations (52 percent), and employee training and development (68 percent). By regularly reassessing the processes, programs and structures in place, nonprofits can understand what motivates—or demotivates—their employees.

Governance and Compliance

From dealing with tax and accounting changes to new data privacy laws and regulations, nonprofits should think of good governance as an imperative, not simply a nice-to-have. Even with limited resources, they must take a proactive approach to regulatory compliance and risk mitigation, because the alternative could mean betraying donor and public trust and doing more harm than good. Earmarking funds to cover compliance costs may be painful initially, but the costs of noncompliance are even greater.

Technology, Equipment and Supplies

People are important to an organization, but so are the technologies, equipment and supplies keeping it running. In addition to jeopardizing employee satisfaction, having outdated IT and equipment can drain already-limited resources by reinforcing operational inefficiencies, weakening impact reporting (56 percent of Nonprofit Standards survey participants cite the lack of adequate technology to gather data on impact as a high or moderate challenge), increasing cyber and data privacy vulnerabilities and more. Nonprofits should invest in technology that can help them advance a larger goal—whether it’s empowering their employees to accomplish more, making their programs more accessible or amplifying their current fundraising efforts.

Cybersecurity and Data Privacy

Trust in the nonprofit world is not only expected, but foundational—a critical part of which is data privacy. Nonprofits must safeguard the data entrusted to and or collected by them as if it were their own. Unfortunately, many fail to invest in cyber or data privacy programs, due to the assumption that they’re too small to be a viable target. However, this often makes them even more appealing and vulnerable to cyberattackers. Security needs to remain a key priority, even amidst multiple projects.

Fundraising Costs

These are the costs associated with seeking, soliciting or securing charitable contributions.

Many investments in this category fall into similar buckets as those outlined above, especially people and technology. Whether it’s spending money to hire and train a fundraising team, or purchasing new fundraising tools that can expand an organization’s reach, putting aside funds to improve visibility will pay off in the long run.

Nevertheless, there are many reasons why organizations don’t invest enough in fundraising. They may be overconfident in their current funding streams and unable to see why more investment is needed when ample funding or a loyal donor base already exists. They may ignore changing donor demographics or technological trends that change the way in which potential donors engage with the causes that are meaningful to them. Or they may view fundraising as a “forced” expense, rather than an investment that can reap dividends down the road. But the reality is, maximizing good also requires maximizing awareness.

Balancing programmatic and operational spending isn’t easy, and requires organizations to assess their operations with a critical business mindset. Altruism without an efficient infrastructure to support it won’t go far—and if organizations aren’t careful about how they spend their money, they’ll fall into the starvation cycle of trying to do infinitely more with much, much less.

Emphasize Financial Due Diligence

Another key component of maximizing good is maintaining financial due diligence. This means not only ensuring that your nonprofit has enough liquidity to function effectively, but also understanding how changing regulatory, tax and financial accounting regulations could ultimately affect the public’s perception of your organization.

Maintaining Sufficient Operating Reserves

Maintaining adequate liquidity is a must for every nonprofit. When organizations encounter funding disruptions or lose a major donor, a healthy supply of operating reserves (liquid, unrestricted net assets) is a critical fiscal safety net to keep programs up and running.

However, liquidity is not a one-size-fits-all metric: The “right” amount of operating reserves varies according to organization size, sector and scope. With that in mind, establishing at least six months of operating reserves is a prudent target for the sector overall. More than half (63 percent) of organizations surveyed in our annual benchmarking survey, Nonprofit Standards, maintain six months or less of operating reserves.

What’s even more worrisome is that few nonprofit leaders consider maintaining adequate liquidity as a significant challenge for their organization. Sixty percent of organizations say liquidity is a low-level challenge, or not a challenge at all.

Why the discrepancy? It could be that many organizations are overconfident in their funding streams—or underestimating the financial loss they would suffer if they were disrupted. Of course, there may also be some nonprofits that are struggling to even stay afloat. However, the importance of having at least some operating reserves—even if they’re only for a few months at the beginning—can’t be stressed enough.

Unfortunately, lacking sufficient liquidity can lead to a not-so-happy ending—as seen by the unlikely demise of many a former nonprofit. Before New York’s Federation Employment and Guidance Service (FEGS) filed for bankruptcy in 2015, for example, nobody saw it coming. The nonprofit was 80 years old and had $260 million in revenues. So, what went wrong? Lurking behind those successes was an unseen $20 million deficit. Nobody—including the board and management—seemed to know there were liquidity and cash flow problems.

Unfortunately, this is not an uncommon scenario. Part of the knowledge gap may have been due to the lack of clarity in the information presented in the financial statements at the time (a topic expanded in greater detail in the next section). However, more generally, it was likely due to the inadequate attention paid to the organization’s overall financial health throughout the years. A nonprofit with faltering liquidity—if addressed too late—may incur skepticism from major donors. However, if addressed early on, it could, instead, inspire an influx of donations from supporters who see a dire need for resources.

To avoid this scenario, nonprofits should consider adopting a “reserve policy” (if they don’t already have one) based on a comprehensive risk analysis. This policy should provide guidance on how (and how much) money they should put into their reserves, under what circumstances the reserves should be used, the process for deciding how to use these reserves, as well as any other restrictions or limitations that ought to be considered. While not a surefire guarantee of survival, having a few months’ worth of operating funds can at least help nonprofits continue their programs while they’re trying to get back up on their feet.

Staying Abreast of Regulatory, Tax & Financial Accounting Changes

Being prepared for the unpredictable is one thing, but nonprofits are often unprepared for even the predictable—including regulatory, tax and accounting changes coming down the pike.

The past few years have been especially busy for nonprofits. Tax reform, for one, provided a significant shift in rules for nonprofits to address. The trifecta of financial accounting changes—including revenue recognition, lease accounting and changes to the presentation of nonprofit financial statements—is another. Some of these deadlines have either already passed or are coming up.

Why do these financial changes matter? Other than being requirements, they affect how nonprofits document their donations and financial statements to their stakeholders—including their Board, donors, constituents and the general public. This, consequently, affects how the latter will assess an organization’s financial health.

One example of this change is the Financial Accounting Standards Board’s (FASB) Accounting Standards Update (ASU) 2016-14, Presentation of Financial Statements of Not-for-Profit Entities, released in 2016. The ASU reclassified the former three existing classes of net assets (unrestricted, temporarily restricted and permanently restricted) into two new classes: 1) net assets without donor restrictions; and 2) those with donor restrictions. Its goal was to provide readers with a better understanding of the resources available to an organization versus those set aside to meet a donor’s intent. Without that distinction, most of an organization’s net assets may be locked up in various ways—such as endowments, property and plant or other restrictions or designations—which may lead stakeholders falsely to believe the funds are available for use when they are not.

Thus, when undergoing the compliance process, nonprofit leaders should be prepared to address any questions about liquidity or cash flow from their stakeholders—especially about how these changes may have affected how their statements were prepared or reported. Maximizing good requires organizations to not only mitigate compliance risk, but to be able to clearly explain all facets of their financial situation.

Inspire Public & Donor Trust

Doing good can be done solo, but maximizing good requires many hands. Nonprofit leaders who wish to take their organization far must learn how to not only shore up initial public and donor trust, but maintain it throughout the years. They must ensure that their current and prospective supporters are able to see, understand and even experience the good they’re doing.

As with any initiative, inspiring public and donor trust has many challenges. Donors today hold nonprofits to higher standards of transparency, accountability and reporting around impact and outcomes than ever before. This is especially true now that the profile of the average donor is changing. Millennials now make up the largest portion of the overall population and have begun to take on a key role in philanthropy worldwide. These donors differ significantly from their predecessors: They not only place a huge emphasis on trust, but also expect faster reporting times, thanks to social media and other technologies. And it’s not only donors who are taking notice, but all of a nonprofit’s stakeholders, including their Board, external partners, volunteers and members.

With such close scrutiny upon them, nonprofits need to get better at not only measuring impact, but reporting it. The vast majority (96 percent) of organizations communicate impact outside of their organization, according to Nonprofit Standards, and many are under increased pressure to demonstrate results and provide further transparency. Forty-eight percent say that more than a quarter of their funders requested more information than was previously required.

Meeting these demands requires increased people-power and enhanced training and education. But it also requires the development of a consistent framework for measuring and reporting impact (cited by 62 percent of survey participants as a high- or moderate-level challenge) and adequate technology to gather data on impact (56 percent). Other common reporting challenges include human resources constraints (66 percent), lack of clear program objectives or key performance indicators (KPIs) to measure against (45 percent), and inadequate financial resources (54 percent).

Nonprofits will need to work hard to bridge these gaps. They will also need to go beyond traditional reporting tactics (i.e. creating an annual report, sending regular email and mail communications, etc.) to meet donors on their turf and on their real-time timeline.

When impact reporting is effective, it really pays off—not only in donations, but in a currency much more valuable long term: loyalty and trust.

Nonprofits want to maximize good, and that’s a good thing.

But to succeed, organizations must look beyond simply expanding their programs and activities to also assess their own core operations. They must ask themselves: Am I sufficiently balancing programmatic spending with necessary infrastructure investments? Emphasizing financial due diligence? Doing all that’s possible to further inspire public and donor trust?

Good intentions are not enough. But good intentions, combined with business smarts, are a winning combination. By spending time on capacity building, organizations will be able to reach a point when they’re not only able to keep their operations running effectively and efficiently, but take it to the next level through scale and strategic growth decisions.

To learn more about these decisions, look out for our next insight, Mission‑Driven Growth.

SHARE