The Steel Industry and Its Place in the American Economy

A History of Steel Production in the United States

The United States has been a major player in the steel market since the 19th century. In the decades after the Civil War, the American steel industry began to take off: annual production was approximately 1.25 million tons in 1880, 10 million tons in 1900, and 24 million tons in 1910, which was by far the greatest of any country and about 40% of the global steel production that year. During this time, the American economy grew to become the largest in the world, largely due to the jobs and economic output coming from the growing steel industry.

Technological advancement throughout the 20th century led to increased production capacity, and both domestic and international demand increased as well. After World War II, steel demand across the world boomed: many countries that were devastated by the war needed steel to rebuild their infrastructure and didn’t have the steel production capacity to meet their needs.

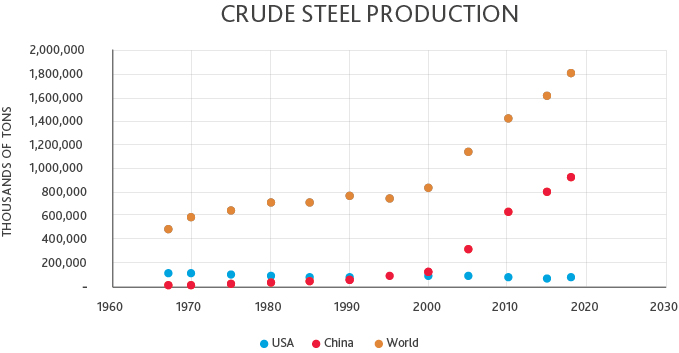

While the steel industry has remained important to the American economy, its influence has declined since the mid-20th century. Crude steel production in 2018 totaled about 73% of 1970 production levels while global production has tripled over that time span. As of March 2018, American steel mills employed about 83,000 workers, while employment regularly exceeded 700,000 workers throughout the 1950s. Large steel mills across the country have closed, and a larger share of production now comes from smaller “specialty” mills.

Several factors led to this decline. The technological advancements made throughout the 20th century allowed companies to produce steel with far less manpower. While jobs were lost in the steel industry, employment in other sectors—like technology—grew, diminishing the relative influence of the steel industry on the American economy. The increase of steel production in other countries has also had a profound impact. After the United States sold steel at low costs to European countries and Japan after World War II, these countries were able to reconstruct their steel mills (in addition to constructing new ones) and eventually no longer needed American steel to meet their domestic demand. As America was falling out of position as the world’s largest steel producer, China was preparing to take its place.

Steel Production in China and its Impact on the Global Market

Chinese steel production has skyrocketed since the turn of the century. In 2000, China produced 127,236 tons of crude steel, representing about 15% of global production (847,057 thousand tons). In 2018, China exceeded the global production in 2000, producing approximately 928,300 thousand tons of crude steel – over 51% of the 1,808,000 thousand tons produced globally in 2018.

Though its production curve looks flat compared to the other two data sets, American steel production has decreased over the past few decades, whereas Chinese production steadily increased until around 2000, when production skyrocketed, bringing global production levels up with it.

For over a decade, the rapid increase of steel supply in China was met with a similar increase in national demand, minimizing the impact of China’s increased production on the global economy. However, in 2014, supply finally began to exceed demand within the country. China found itself with a surplus of steel and began to flood the global market with unprecedented amounts of steel. From 2014 to 2015, Chinese steel exports increased from 45 million tons to 97 million tons. China’s 2015 exports were higher than the entirety of American steel production (79 million tons).

While some might have expected China to ease back on their production and, in some cases, close facilities, certain political roadblocks kept most mills open and most steelworkers employed. In China, steel mills are governed by regional Communist Party officials. These officials are incentivized to keep the mills open. Closing a steel mill would lead to a sharp increase in unemployment and the civil unrest that comes along with it, so the production levels continued to increase. Steel production is also seen culturally as an indicator of success and a symbol of pride in China, so there’s a collective motivation to keep the mills open.

So, with this massive steel surplus, would steel mills all around the world shut down?

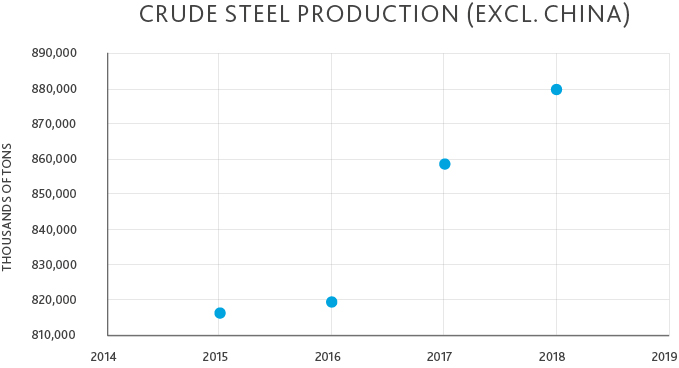

Believe it or not, China’s 2014 surplus hasn’t slowed down the rest of the world. In fact, global steel production, excluding China, increased by seven percent from 2015 to 2018. China is not alone in viewing steel production as a symbol of pride and industrial esteem – many other governments, including those of Italy and the United Kingdom, have provided monetary or legislative support to domestic steel producers. Even the American government—whose rise to a global superpower was intertwined with its domination of the steel industry—feels a sense of pride in its steel production and concern over the wellbeing American steel companies that often influences policy.

Quality Concerns Regarding Chinese Steel

One way that the Chinese government has dealt with high production levels is to incentivize the production of higher-quality steel products. They do this by offering tax rebates for steel alloy exports. Unfortunately, a loophole in Chinese tax law has led to an unsafe development in Chinese steel alloy manufacturing. Manufacturers can qualify for tax rebates by putting a very small percentage of cheap metals in their steel, which wouldn’t meet typical alloy standards in the United States, Japan, or Europe. Before 2015, Chinese steel mills produced steel alloys with Boron. Adding Boron, which hardens the steel, is very cheap and allowed the manufacturers to qualify for the tax rebate, which then allowed them to export the steel at very low prices and still make a profit.

To make matters worse, the addition of Boron has negative effects on the properties of steel. Steel alloys containing Boron in excess of five parts per million are prone to developing cracks when used in welding. The cracks can take days to develop, so it’s possible that they might not be noticed by the welder.

Ultimately, upon discovery that this loophole was being widely exploited, the Chinese government took away the rebates for Boron alloys in 2015, but very little was done to eliminate rebates for other alloys. Chromium subsequently became the top alloy produced, with just a 0.3% chromium steel alloy granting manufacturers the ability to claim a 5-13% tax rebate. Copper alloys, which can have the same brittleness issues as Boron alloys, are also still manufactured for a rebate. Although they’re more expensive, Titanium alloys would also qualify for a rebate and would likely be the next to be mass-produced should rebates be canceled for Chromium and Copper. Until the rebates are canceled altogether, Chinese manufacturers will look for loopholes to keep prices as low as possible while still profiting from exports.

Tariffs

Of course, so much focus has been placed on the Chinese steel industry lately because of the tariffs that are being levied on Chinese steel imports. After months of threatening to impose tariffs, President Donald Trump imposed a 25% tax on almost all imported steel (not just steel from China) in March 2018. These tariffs allowed American steel prices to exceed the global average steel prices for most of 2018. Even though steel from other countries was often cheaper than American steel even with the tariffs, the price gap closed significantly, which is enough to greatly benefit American steel companies.

If manufacturers of products with imported steel subject to tariffs are paying more for raw materials, the price of the consumer goods that they make may increase to cover the higher costs. These price increases could cost households hundreds or even thousands of dollars per year if manufacturers aren’t able to absorb the cost increases themselves and have to pass them to consumers.

Some manufacturers could be at risk too. Namely, American manufacturers that sell their products internationally could be paying more for their raw materials than their international competition if they use steel subject to the 25% tariffs. If impacted domestic manufacturers aren’t able to absorb the costs, they may need to increase their prices for customers, which could hurt their international competitiveness. If international competition gets an upper hand, American companies may struggle to keep up, which can lead to a loss of profit and worker layoffs.

While the increased tariffs on hundreds of other Chinese products have dominated the news cycle, steel tariffs have remained constant, even while tariffs for steel from other countries are being lifted. This is expected to bring the cost of American steel closer to the global average, while partially negating some of the aforementioned effects of steel tariffs.

Looking Ahead

China’s steel production has continued to increase to supply China’s rapidly-growing property investment. Experts fear, however, that this continued increase in production may outlast the boom in property investment, and the global steel surplus will flood the market, much like what happened in 2014.

The trade war between China and the United States appeared to be close to yet another escalation in May 2019, when President Trump threatened to impose new tariffs on the rest of goods imported from China; however, a truce was declared before these tariffs went into effect. On June 29, 2019, President Trump and Chinese President Xi Jinping met at the G20 Summit to discuss trade. Among other agreements, President Trump agreed not to implement these tariffs for the time being.

If negotiations with China progress, and if steel tariffs are included in those negotiations, there’s a chance they’ll be lifted. Until then, manufacturers using imported steel may continue to pay higher costs, which consumers may feel in their wallets if manufacturers can’t absorb the costs themselves.

https://www.worldsteel.org/steel-by-topic/statistics/steel-statistical-yearbook.html

http://www.nationalmaterial.com/brief-history-american-steel-industry/

https://money.cnn.com/2018/03/09/news/companies/american-steel-history/index.html

https://www.npr.org/2018/03/08/591637097/china-churns-out-half-the-worlds-steel-and-other-steelmakers-feel-pinched

https://www.economist.com/the-economist-explains/2016/05/05/why-the-world-has-too-much-steel

https://www.economist.com/business/2019/06/29/the-european-steel-industry-is-being-clobbered

Joseph Ash Galvanizing

https://uk.reuters.com/article/uk-usa-trade-china-steel-factbox/factbox-taxing-issue-chinas-controversial-steel-rebate-policy-idUKKBN1KF0DY

https://www.reuters.com/article/us-china-steel-exports/gaming-the-system-china-steel-exporters-look-for-tax-advantage-idUSKBN0TS2ST20151209

https://www.economist.com/special-report/2019/05/16/the-trouble-with-putting-tariffs-on-chinese-goods

https://www.wsj.com/articles/trump-tariffs-and-china-spell-trouble-for-american-steel-11558524149

https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-trade-china-timeline/timeline-key-dates-in-the-us-china-trade-war-idUSKCN1SE2OZ

CNBC

https://www.businessinsider.com/us-china-trade-war-truce-might-not-lead-to-deal-2019-7

SHARE