Healthcare Takeaways from Trump’s Proposed FY21 Budget

The Trump administration released its proposed FY21 budget prior to the novel COVID-19 pandemic and before declaring a national state of emergency in the United States. We know that right now, every organization—including BDO—is focused on the well-being of families, colleagues and our communities. We’ll continue to monitor the situation and provide guidance on how developments around COVID-19 could impact healthcare organizations’ finances and larger operations to help organizations manage the situation effectively. For information on how to secure your business in the wake of COVID-19, please visit www.bdo.com/COVID-19.

If Implemented, Plans Would Add to Financial Pressures Facing Hospitals.

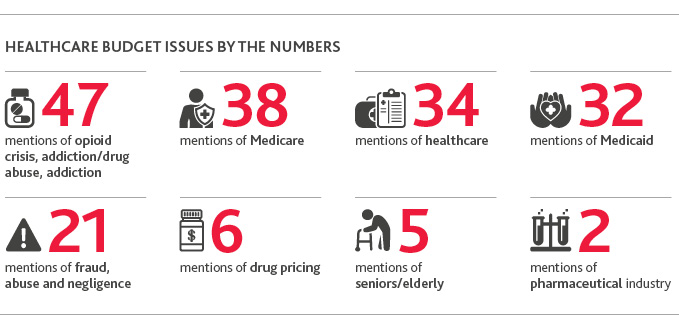

By Chad Krcil & Venson WallinOn Feb. 10, the Trump administration released its proposed budget for FY21, which focuses heavily on healthcare and contains several plans to reform Medicare and Medicaid.

Though it’s unlikely that many of the proposals in their current form will come to fruition, CMS is likely to look to them for guidance on how to set its inpatient and outpatient rules for 2021. Depending on what the final versions of the rules look like, they could dramatically reduce payments to hospitals—already facing intense downward financial pressures.

Overall, the goals of the proposed budget are to:

- Focus on patient-centric markets

- Deliver value, improve patient outcomes and mitigate health crises

- Deliver Medicare savings of $756 billion over 10 years

- Extend Medicare solvency for the next 25 years

Healthcare organizations—hospitals and outpatient facilities alike—should be mindful of seven key proposals that could impact their reimbursement levels:

1. Uncompensated Care (UCC) PaymentsCurrently, Medicare makes two payments to hospitals serving a disproportionate share of low-income patients:

- Traditional disproportionate share hospital (DSH) payments

- UCC payments

- Total uncompensated care payments would be equal to FY19 funding levels, updated annually according to the consumer price index (CPI) for urban consumers effective for FY22.

- The general fund would pay for UCC payments instead of the Medicare trust fund.

- Medicare would base UCC payments to hospitals on their share of charity care and non-Medicare bad debts, according to numbers reported via the Medicare cost report.

- Medicare payment policy would align with private insurers that do not cover uncompensated care.

- DSH payments would stay the same.

2. Medicaid Payments

Under the current state, most Medicaid expansion states have reported relying on the general fund to finance Medicaid expansion under the Affordable Care Act (ACA), while others have reported relying on provider taxes or savings realized through the expansion, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation. In FY18, for example, Medicaid spending totaled $593 billion, with nearly 63% paid by the federal government and almost 38% paid by states.

Proposed changes in the FY21 budget include:

- Imposing new requirements on beneficiaries wishing to enroll

- Reducing the share of Medicaid bills that the federal government pays: Currently under ACA, states can opt to expand Medicaid coverage to low income adults with the federal government picking up 90% of reimbursement due to this expansion. The budget proposes to eliminate this federal match for the expansion.

- Extending state Medicaid DSH allotment reductions for an additional five years through FY30

- Increasing co-pays for use of hospital emergency departments for non-emergency services

- Limiting Medicaid reimbursement for public health hospitals so payments do not exceed cost of providing services to Medicaid beneficiaries

3. Payments to On-Campus Outpatient Hospital Departments (OHD)

Under the current state, Medicare reimburses on-campus OHD more than physician offices.

Proposed changes in the FY21 budget include:

- Beginning in calendar year 2021, payments to on-campus OHD and physician offices would be site neutral—except in the case of rural hospitals, in an effort to help them combat the especially strong downward financial pressures they’re facing.

- The difference Medicare pays in various settings for the same services would be eliminated.

4. Payments to Hospital-Owned Physician Offices Located off Campus

Under the current state, facilities located off campus—like emergency rooms, cancer hospitals and grandfathered departments billing under the outpatient prospective payment system or that were under construction before Nov. 2, 2015—receive higher reimbursement rates than providers reimbursed under the physician fee schedule.

Proposed changes in the FY21 budget include:

- Beginning in calendar year 2021, all off-campus outpatient departments would be reimbursed according to the physician fee schedule.

- Payments to OHD and physician offices would be site neutral, regardless of hospital ownership or facility type.

5. Medicare Bad Debts

Under the current state, Medicare pays 65% of Medicare bad debt.

Proposed changes in the FY21 budget include:

- Medicare bad debt payments for DSH-eligible hospitals are eliminated—excluding rural hospitals.

- Medicare payment policies are aligned with private insurers that do not cover uncompensated care.

6. Inpatient Hospital Wage Index

Today’s system for wage index creates disparities between high- and low-wage index hospitals.

Proposed changes in the FY21 budget include:

- A demonstration test for comprehensive wage index reform, which would use the commuting data of the labor market area by zip code to:

- Improve hospital wage index

- Decrease differences in wage index and payments between nearby hospitals

- Address differences between low- and high-wage hospitals

- Protect access to rural area healthcare

- Establishing alternative sources of a wage index

- Eliminating rural floor and other reclassifications and special payment adjustments

- Imposing civil monetary penalties for hospitals submitting inaccurate and/or incomplete data

7. Graduate Medical Education Payments

Under the current state, medical education payments for Medicare, Medicaid and the Children’s Hospital Graduate Medical Education Program are disparate.

Proposed changes in the FY21 budget include:

- Consolidating those payments into a grant program for teaching hospitals

- Making funds available that would equal Medicare and Medicaid’s Graduate Medical Education payments plus 2017 Children’s Hospital Graduate Medical Education spending, adjusted for inflation

- Basing payments to hospitals on number of residents up to a cap and the hospital’s inpatient days for Medicare and Medicaid

BDO’s Take on Resulting Pressure Points

The collective plans within the proposed FY21 budget create three key pressure points across the U.S. health ecosystem:1. Critical Need to Monitor Federal Communications around COVID-19 Response and Relief

COVID-19 will further exacerbate an already challenging financial outlook for healthcare organizations. As the situation evolves, hospitals will feel intense pressure to identify ways to protect reimbursement levels and margins. Remaining cognizant of the Trump administration’s COVID-19 relief packages, and identifying ways they can obtain additional reimbursement through them, will be critical for hospitals. As the situation evolves each day, they’ll need to closely monitor communications from the Trump administration and appropriate health agencies including the CMS, FEMA, HHS, CDC and the WHO.

2. Increased financial pressure on hospitals

For hospitals, which comprise 73% of healthcare CFOs concerned about government reimbursement risk, the proposed changes would collectively result in increased financial pressure. This is especially true for hospitals serving a high population of low-income patients and already struggling to maintain sustainable margins. To add salt to the wound, many DSH hospitals also happen to be those eligible for the already under-fire 340b program, which requires drug manufacturers to provide outpatient drugs at reduced prices to certain healthcare organizations.

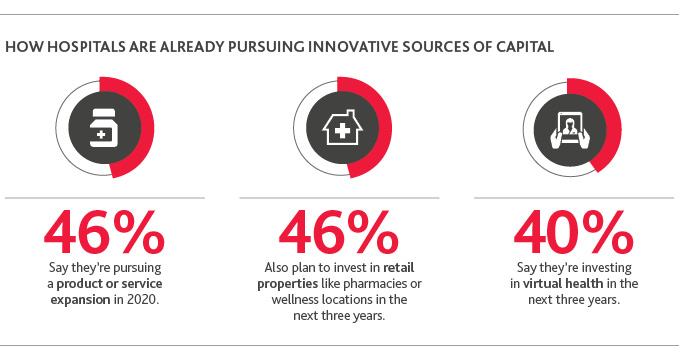

3. Innovative sources of capital become more critical

Many hospitals will need to identify how these changes will impact them operationally and financially and work to enhance reimbursement in every way they can. At the same time, they’ll need to look for new sources of funding as traditional ones continue to come under fire. These could include investing in innovative funds, product or service development, refocusing real estate assets or transforming the overall consumer experience.

4. Reduced incentives for Medicaid managed care

The combined cuts to Medicaid expansion dollars and the rollback of the ACA’s individual mandate remove incentives for individuals not covered through an employer plan to sign up for coverage. This, in turn, largely removes any type of incentives that managed care plans had to participate in Medicaid managed care, and could have negative implications for access to care among certain patient populations.

SHARE