Core of the Core Deposit Intangible – Valuation and Trends

As bank-related mergers continue to accelerate in 2021 in the face of pent-up transaction demand, the financial reporting requirements related to Accounting Standards Codification 805 (ASC 805), Business Combinations, have brought the Core Deposit Intangible (CDI) back into focus. The CDI is typically the primary intangible asset identified as part of a bank transaction.

How to ID the CDI

The CDI has value as core deposits, typically defined as interest and non-interest- bearing checking accounts, savings and money market accounts, provide a below market source of funds to the acquirer in a business combination. The CDI is considered a finite intangible asset as deposit classes tend to close out over time for several reasons including competition, mortality and migration. However, these deposit classes are termed “core” due to their stability as a source of funding. Other fixed-term deposit classes like retail certificates of deposit under $100,000 may, on occasion, yield intangible asset value as facts and circumstances dictate, but may be excluded from the core deposit base due to their higher proclivity to migration, as well as in cases where interest and maintenance costs are greater than the cost of an alternative funding source.

The Core of the Approach

The accepted approach for valuing the CDI is referred to as the Cost Savings Approach, which is a variant of an income approach. The Cost Savings Approach takes into consideration the wasting nature of an asset for the reasons noted above and then determines the spread between the all-in cost of core deposits acquired (interest and net maintenance costs) and the cost of an alternative funding source over the estimated life of the core deposit base. The cost savings are tax effected and discounted to present value using a risk adjusted discount rate. Finally, a tax amortization benefit is added to conclude on fair value.

All-in costs related to the CDI typically include:

- Future interest costs based on historical trends and future expectations about deposit pricing, and

- Net maintenance costs comprised of the difference between the costs to service, the opportunity cost of reserves and float and fee income.[1]

A small but persistent number of firms employ a financial instrument approach to valuing the CDI. In these situations, pre-tax cash outflows are discounted by a market rate (e.g., FHLB Advance Rate). The CDI however is not a financial instrument as stated in ASC 825, Financial Instruments:

“In estimating the fair value of deposit liabilities, a financial entity shall not take into account the value of its long-term relationships with depositors, commonly known as core deposit intangibles, which are separate intangible assets, not financial instruments.”

Based on this assessment, the treatment of the CDI as a financial instrument can, and often does, lead to inaccurate CDI fair value conclusions.

Core Trends in CDI Premiums

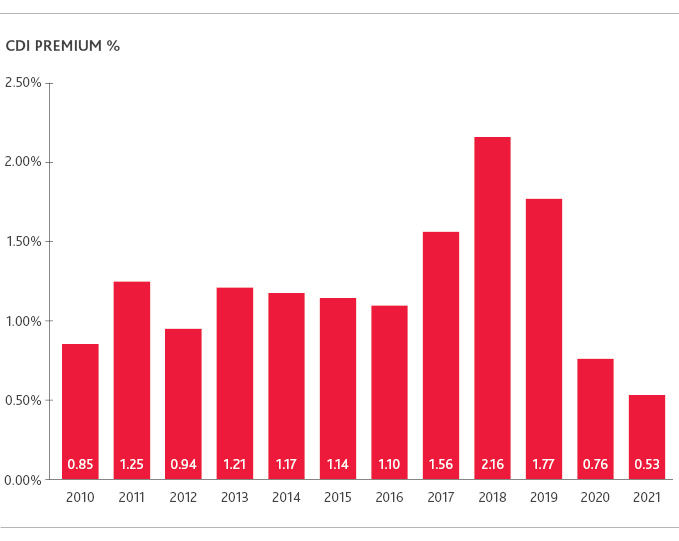

Interest rate movements are among the most significant factors in the determination of CDI value. In a low interest rate environment, which was exacerbated by the Fed cutting rates in the face of a global pandemic, CDI values in 2020 and 2021 have trended to their lowest levels in the past decade. As deposit accounts reached an implied pricing floor, the low interest rate environment compressed the spread between deposits and alternative funds. Based on our review of data stretching back over a decade, this fact pattern seems to be borne out as CDI values as a percent of total core deposit liabilities (i.e., CDI premiums) have shrunk after seeing a pop in value in the years leading up to 2018.

Source: S&P Market Intelligence

Core Tenets of CDI Accounting

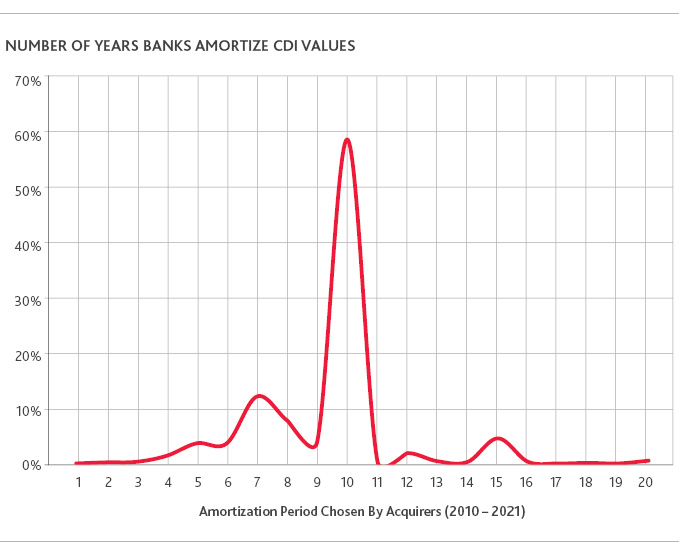

According to the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) guidance, if an income approach is used to develop the value of an intangible asset, the period of projected cash flows should be considered when choosing a useful life. While accounting interpretations are a matter for a client and its independent auditors, we note that based on data from acquisitions for which the CDI detail was reported, most banks select a ten-year amortization term for the CDI (see the chart below). This is supported by prior statements by the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC), which suggests that in most cases the useful life for the CDI would not exceed 10 years. As best practice however, banks should carefully consider historical patterns of attrition for the CDI as well as the period over which CDI cash flows are expected to be received, when selecting a useful life.

Source: S&P Market Intelligence

Gain a Clear View of the CDI Acquired

The CDI represents long-term depositor relationships and derives its value from being a low-cost source of deposit funding. Although CDI values have recently trended downward due in part to market trends in interest rates, they remain an integral and unique component of bank transactions. The standard approach to determining the fair value of the CDI is the Cost Savings Approach. One should carefully consider their valuation service provider when entering into a bank transaction where core deposits are being acquired. BDO, through its experience and qualifications, helps minimize financial reporting risk by providing reasonable and supportable valuations for the CDI acquired in a banking transaction.

[1] Due in part to the COVID-19 pandemic, it should be noted that in March 2020 the Federal Reserve reduced reserve requirements, which typically range from 3 to 10 percent, to zero percent. Additionally, technology improvements in fund transfers have led to diversity in practice on the inclusion of float costs, which refer to the opportunity cost of not being able to invest non-cash deposits between the time customer deposit accounts are credited and when they become available to the bank.

SHARE